A few radical philosophers like Xenophanes of Colophon were already beginning to label the poets' tales as blasphemous lies in the 6th century BC; Xenophanes had complained that Homer and Hesiod attributed to the gods "all that is shameful and disgraceful among men; they steal, commit adultery, and deceive one another".

This line of thought found its most sweeping expression in Plato's Republic and Laws. Plato created his own allegorical myths (such as the vision of Er in the Republic), attacked the traditional tales of the gods' tricks, thefts and adulteries as immoral, and objected to their central role in literature.

Plato's criticism (he called the myths "old wives' chatter") was the first serious challenge to the homeric mythological tradition.

For his part Aristotle ctiticized the Pre-socratic quasi-mythical philosophical approach and underscored that "Hesiod and the theological writers were concerned only with what seemed plausible to themselves, and had no respect for us.

But it is not worth taking seriously writers who show off in the mythical style; as for those who do proceed by proving their assertions, we must cross-examine them".

Nevertheless, even Plato did not manage to wean himself and his society from the influence of myth; his own characterization for Socrates is based on the traditional homeric and tragic patterns, used by the philosopher to praise the righteous life of his teacher:

"But perhaps someone might say: "Are you then not ashamed, Socrates, of having followed such a pursuit, that you are now in danger of being put to death as a result?"

But I should make to him a just reply: "You do not speak well, Sir, if you think a man in whom there is even a little merit ought to consider danger of life or death, and not rather regard this only, when he does things, whether the things he does are right or wrong and the acts of a good or a bad man.

For according to your argument all the demigods would be bad who died at Troy, including the son of Thetis, who so despised danger, in comparison with enduring any disgrace, that when his mother (and she was a goddess) said to him, as he was eager to slay Hector, something like this,

My son, if you avenge the death of your friend Patroclus and kill Hector, you yourself shall die; for straightway, after Hector, is death appointed unto you ."

Hanson and Heath estimate that Plato's rejection of the Homeric tradition was not favorably received by the grassroots Greek civilization. The old myths were kept alive in local cults; they continued to influence poetry, and to form the main subject of painting and sculpture.

More sportingly, the 5th century BC tragedian Euripides often played with the old traditions, mocking them, and through the voice of his characters injecting notes of doubt. Yet the subjects of his plays were taken, without exception, from myth.

Many of thses plays were written in answer to a predecessor's version of the same or similar myth. Euripides impugns mainly the myths about the gods and begins his critique with an objection similar to the one previously expressed by Xenocrates: the gods, as traditionally represented, are far too crassly anthropomorphic.

Hellenistic and Roman Rationalism

During the Hellenistic period, mythology took on the prestige of elite knowledge that marks its possessors as belonging to a certain class. At the same time, the skeptical turn of the Classical age became even more pronounced.

Greek mythographer Euhemerus established the tradition of seeking an actual historical basis for mythical beings and events. Although his original work (Sacred Scriptures) is lost, much is known about it from what is recorded by Diodorus and Lactantius.

Rationalizing hermeneutics of myth became even more popular under the Roman Empire, thanks to the physicalist theories of Stoic and Epicurean philosophy.

Stoics presented explanations of the gods and heroes as physical phenomena, while the euhemerists rationalized them as historical figures.

At the same time, the Stoics and the Neoplatonists promoted the moral significations of the mythological tradition, often based on Greek etymologies.

Through his Epicurean message, Lucretius had sought to expel superstitious fears from the minds of his fellow-citizens.

Livy, too, is sceptical about the mythological tradition and claims that he does not intend to pass judgement on such legends (fabulae).

The challenge for Romans with a strong and apologetic sense of religious tradition was to defend that tradition while conceding that it was often a breeding-ground for superstition.

The antiquarian Varro, who regarded religion as a human institution with great importance for the preservation of good in society, devoted rigorous study to the origins of religious cults.

In his Antiquitates Rerum Divinarum (which has not survived, but Augustine's City of God indicates its general approach) Varro argues that whereas the superstitious man fears the gods, the truly religious person venerates them as parents. In his work he distinguished three kinds of gods:

The gods of nature: personifications of phenomena like rain and fire.

The gods of the poets: invented by unscrupulous bards to stir the passions.

The gods of the city: invented by wise legislators to soothe and enlighten the populace.

Roman Academic Cotta ridicules both literal and allegorical acceptance of myth, declaring roundly that myths have no place in philosophy.

Cicero is also generally disdainful of myth, but, like Varro, he is emphatic in his support for the state religion and its institutions. It is difficult to know how far down the social scale this rationalism extended.

Cicero asserts that no one (not even old women and boys) is so foolish as to believe in the terrors of Hades or the existence of Scyllas, centaurs or other composite creatures, but, on the other hand, the orator elsewhere complains of the superstitious and credulous character of the people. De Natura Deorum is the most comprehensive summary of Cicero's this line of thought.

Syncretizing trends

During the Roman era appears a popular trend to syncretize multiple Greek and foreign gods in strange, nearly unrecognizable new cults. Syncretization was also due to the fact that the Romans had little mythology of their own, and inherited the Greek mythological tradition; therefore, the major Roman gods were syncretized with those of the Greeks.

In addition to this combination of the two mythological tradition, the association of the Romans with eastern religions led to further syncretizations. For instance, the cult of Sun was introduced in Rome after Aurelian's successful campaigns in Syria.

The asiatic divinities Mithras (that is to say, the Sun) and Ba'al were combined with Apollo and Helios into one Sol Invictus, with conglomerated rites and compound attributes.

Apollo might be increasingly identified in religion with Helios or even Dionysus, but texts retelling his myths seldom reflected such developments. The traditional literary mythology was increasingly dissociated from actual religious practice.

The surviving 2nd century collection of Orphic Hymns and Macrobius's Saturnalia are influenced by the theories of rationalism and the syncretizing trends as well.

The Orphic Hymns are a set of pre-classical poetic compositions, attributed to Orpheus, himself the subject of a renowned myth. In reality, these poems were probably composed by several different poets, and contain a rich set of clues about prehistoric European mythology.

The stated purpose of the Saturnalia is to transmit the Hellenic culture he has derived from his reading, even though much of his treatment of gods is colored by Egyptian and North African mythology and theology (which also affect the interpretation of Virgil). In Saturnalia reappear mythographical comments influenced by the euhemerists, the Stoics and the Neoplatonists.

Modern Interpretations

In Roman religion the worship of the Greek god Apollo was combined with the cult of Sol Invictus.

The genesis of modern understanding of Greek mythology is regarded by some scholars as a double reaction at the end of the eighteenth century against "the traditional attitude of Christian animosity", in which the Christian reinterpretation of myth as a "lie" or fable had been retained. In Germany, by about 1795, there was a growing interest in Homer and Greek mythology. In Göttingen Johann Matthias Gesner began to revive Greek studies, while his successor, Christian Gottlob Heyne, worked with Johann Joachim Winckelmann, and laid the foundations for mythological research both in Germany and elsewhere.

Comparative and Psychoanalytic Approaches

The development of comparative philology in the 19th century, together with ethnological discoveries in the 20th century, established the science of myth. Since the Romantics, all study of myth has been comparative. Wilhelm Mannhardt, Sir James Frazer, and Stith Thompson employed the comparative approach to collect and classify the themes of folklore and mythology. In 1871 Edward Burnett Tylor published his Primitive Culture, in which he applied the comparative method and tried to explain the origin and evolution of religion.

Tylor's procedure of drawing together material culture, ritual and myth of widely separated cultures influenced both Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell. Max Müller applied the new science of comparative mythology to the study of myth, in which he detected the distorted remains of Aryan nature worship. Bronislaw Malinowski emphasized the ways myth fulfills common social functions. Claude Lévi-Strauss and other structuralists have compared the formal relations and patterns in myths throughout the world.

Sigmund Freud introduced a transhistorical and biological conception of man and a view of myth as an expression of repressed ideas. Dream interpretation is the basis of Freudian myth interpretation and Freud's concept of dreamwork recognizes the importance of contextual relationships for the interpretation of any individual element in a dream. This suggestion would find an important point of rapprochment between the structuralist and psychoanalytic approaches to myth in Freud's thought.

Carl Jung extended the transhistorical, psychological approach with his theory of the "collective unconscious" and the archetypes (inherited "archaic" patterns), often encoded in myth, that arise out of it. According to Jung, "myth-forming structural elements must be present in the unconscious psyche". Comparing Jung's methodology with Joseph Campbell's theory, Robert A.

Segal concludes that "to interpret a myth Campbell simply identifies the archetypes in it. An interpretation of the Odyssey, for example, would show how Odysseus’s life conforms to a heroic pattern. Jung, by contrast, considers the identification of archetypes merely the first step in the interpretation of a myth". Karl Kerenyi, one of the founders of modern studies in Greek mythology, gave up his early views of myth, in order to apply Jung's theories of archetypes to Greek myth.

Origin Theories

There are various modern theories about the origins of Greek mythology. According to the Scriptural Theory, all mythological legends are derived from the narratives of the Scriptures, though the real facts have been disguised and altered.

According to the Historical Theory all the persons mentioned in mythology were once real human beings, and the legends relating to them are merely the additions of later times. Thus the story of Aeolus is supposed to have risen from the fact that Aeolus was the ruler of some islands in the Tyrrhenian Sea.

The Allegorical Theory supposes that all the ancient myths were allegorical and symbolical. While the Physical Theory subscribed to the idea that the elements of air, fire, and water were originally the objects of religious adoration, thus the principal deities were personifications of these powers of nature.

Max Müller attempted to understand an Indo-European religious form by tracing it back to its Aryan, "original" manifestation. In 1891, he claimed that "the most important discovery which has been made during the nineteenth century with respect to the ancient history of mankind was this sample equation: Sanskrit Dyaus-pitar = Greek Zeus = Latin Jupiter = Old Norse Tyr". In other cases, close parallels in character and function suggest a common heritage, yet lack of linguistic evidence makes it difficult to prove, as in the comparison between Uranus and the Sanskrit Varuna or the Moirae and the Norns.

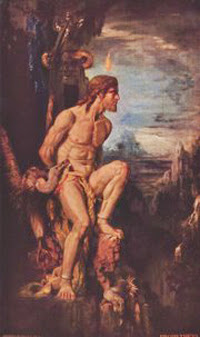

Jupiter et Thétis.

Source:Wikipedia

Archaeology and mythography, on the other hand, has revealed that the Greeks were inspired by some of the civilizations of Asia Minor and the Near East. Adonis seems to be the Greek counterpart - more clearly in cult than in myth - of a Near Eastern "dying god". Cybele is rooted in Anatolian culture while much of Aphrodite's iconography springs from Semitic goddesses.

There are also possible parallels between the earliest divine generations (Chaos and its children) and Tiamat in the Enuma Elish. According to Meyer Reinhold, "near Eastern theogonic concepts, involving divine succession through violence and generational conflicts for power, found their way into Greek mythology".

In addition to Indo-European and Near Eastern origins, some scholars have speculated on the debts of Greek mythology to the pre-Hellenic societies: Crete, Mycenae, Pylos, Thebes and Orchomenos. Historians of religion were fascinated by a number of apparently ancient configurations of myth connencted with Crete (the god as bull, Zeus and Europa, Pasiphaë who yields to the bull and gives birth to the Minotaur etc.)

Professor Martin P. Nilsson concluded that all great classical Greek myths were tied to Mycenaen centres and were anchored in pehistoric times. Nevertheless, according to Burkert, the iconography of the Cretan Palace Period has provided almost no confirmation for these theories.

Motifs in Western Art and Literature

Aphrodite and Adonis.

The widespread adoption of Christianity did not curb the popularity of the myths. With the rediscovery of classical antiquity in Renaissance, the poetry of Ovid became a major influence on the imagination of poets, dramatists, musicians and artists.

From the early years of Renaissance, artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael, portrayed the pagan subjects of Greek mythology alongside more conventional Christian themes.

Through the medium of Latin and the works of Ovid, Greek myth influenced medieval and Renaissance poets such as Petrarch, Boccaccio and Dante in Italy.

Botticelli's The Birth of Venus.

In Northern Europe, Greek mythology never took the same hold of the visual arts, but its effect was very obvious on literature. The English imagination was fired by Greek mythology starting with Chaucer and John Milton and continuing through Shakespeare to Robert Bridges in the 20th century. Racine in France and Goethe in Germany revived Greek drama, reworking the ancient myths.

Although during the Enlightenment of the 18th century reaction against Greek myth spread throughout Europe, the myths continued to provide an important source of raw material for dramatists, including those who wrote the libretti for many of Handel's and Mozart's operas.

By the end of the 18th century, Romanticism initiated a surge of enthusiam for all things Greek, including Greek mythology. In Britain, new translations of Greek tragedies and Homer inspired contemporary poets (such as Alfred Lord Tennyson, Keats, Byron and Shelley) and painters (such as Lord Leighton and Lawrence Alma-Tadema). Christoph Gluck, Richard Strauss, Jacques Offenbach and many others set Greek mythological themes to music.

American authors of the 19th century, such as Thomas Bulfinch and Nathaniel Hawthorne, held that the study of the classical myths was essential to the understanding of English and American literature. In more recent times, classical themes have been reinterpreted by dramatists Jean Anouilh, Jean Cocteau, and Jean Giraudoux in France, Eugene O'Neill in America, and T.S. Eliot in Britain and by novelists such as the James Joyce and the André Gide.